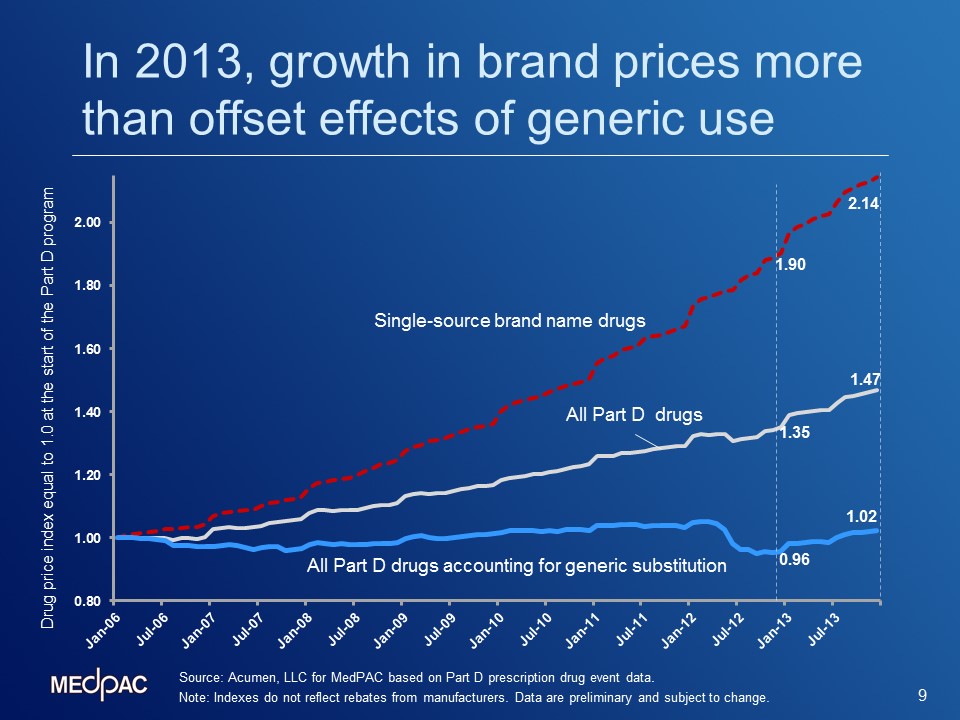

Evidence suggests that price growth for brand-name drugs is beginning to drive growth in average prices of all drugs covered under Part D. The graph below, presented at MedPAC’s January meeting, shows indexes of average prices since the start of the Part D program. Although the indexes exclude rebates and discounts, they are important to monitor because gross prices affect the numbers of enrollees who reach the Part D benefit’s coverage gap and catastrophic threshold, as well as certain cost-sharing amounts. Overall, prices rose 47 percent between January 2006 and December of 2013. When generic substitution is taken into account, prices only rose by 2 percent over the same period, demonstrating that the shift from brands to generics has had a significant effect on keeping Part D prices low. The timing of drugs moving off-patent and efforts by the Part D plans resulted in enrollees using more generics, and therefore helped constrain overall Part D price growth.

However, a closer look at increases in the indexes during 2013 suggests that growth in brand-name prices began to overtake the moderating influence of generics. As the graph illustrates, between 2006 and 2013, prices of single-source brand-name drugs grew by 114 percent (from 1.00 to 2.14). Additionally, between December 2012 and December 2013, the index of Part D prices that accounts for generic substitution grew at the highest year-over-year growth rate observed since the program began. The 2013 increase in the average price index occurred even as the share of generic prescriptions in Part D rose from 81 percent in 2012 to 84 percent in 2013. This suggests that while generics have played an important role in constraining overall price growth, brand price growth began to have a more dominating effect.

Going forward, there is likely to be increased upward pressure on drug prices. Many industry reports (e.g., those published by the IMS Institute and many pharmacy benefit managers) confirm that 2012 was a peak year for patent expirations; meaning there is less opportunity to offset price increases with new generics. Another major source of upward pressure will come from the continued introduction of higher-priced biologics and specialty drugs by the manufacturers. According to a report by PricewatershouseCoopers, FDA approvals of specialty products have surpassed those of traditional drugs, and an analysis by the IMS Institute shows strong growth in the specialty drug share of the research and development pipeline.

A related issue is high launch prices for new specialty drugs, some for therapies that treat broad populations. Some of these medications have faced intense scrutiny in the media and from Congressional leaders and have been criticized as exorbitantly costly. The Commission took a closer look at one example: How treatments for hepatitis C, may affect the Medicare program.

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne virus that causes inflammation of the liver.[1] The hepatitis C virus (HCV) can remain asymptomatic for years, even decades, but can also lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, and higher risk of liver cancer. An estimated 3 million people in the United States have HCV, many without realizing it, and the virus is disproportionately concentrated among baby boomers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015). As of January 2015, about 363,000 Medicare beneficiaries (1.7 percent of the fee-for-services (FFS) population) had been diagnosed with HCV (Segal 2015). Prevalence rates for low income subsidy (LIS) enrollees in Part D are 6 times higher than for non-LIS enrollees: 3.7 percent versus 0.6 percent.

New oral therapies for patients with HCV can substantially reduce or eliminate viral load, may halt progression of disease, and are much more tolerable than older treatments. However, prices for the new drugs are very high: Sovaldi was first offered in December 2013 at $84,000 per treatment regime, or $1,000 per pill. More recently, the FDA approved other HCV therapies and Gilead (Sovaldi’s manufacturer) began offering rebates that lowered the price by about 40 percent (Loftus 2014). Initial data support that new HCV drugs can substantially increase the number of patients achieving a sustained virologic response compared with previous therapies. Even with these benefits, some have questioned the prices. A 2014 comparative clinical and cost effectiveness analysis of Olysio and Sovaldi found that even though newer agents may prevent more liver events such as cancer or transplantation, over a 20-year period, those fewer events would only offset three-quarters of the incremental cost of the new drugs. If a large number of patients were treated, “the clinical advantages of newer treatment regimens would come with a substantial potential impact on health care budgets” (Tice et al. 2014).

The use of new hepatitis C therapies has had a significant impact on Part D spending. Medicare Trustees estimate that in 2014, Part D program payments increased by nearly 15 percent, and they attributed the size of the increase to use of new hepatitis C drugs (Boards of Trustees 2015). As of January 2015, about 57,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries (only 16 percent of those identified as having HCV) had filled at least one prescription for an HCV drug (Segal 2015). Nevertheless in 2014, gross Part D spending for new HCV drugs before rebates was $4.8 billion, and as of June 30, 2015, the comparable figure had reached $4.6 billion (Committee on Finance 2015). Since all Part D enrollees with HCV must have reached the out-of-pocket threshold and many likely had assistance with cost sharing through the LIS, the Medicare program paid for the vast majority of new HCV spending.

[1] Today, the most common way people become infected with hepatitis C is by sharing needles or equipment to inject drugs, but the virus can also be transmitted through contact with infected blood (e.g., needle sticks in health care settings or, prior to 1992, blood transfusions) or less commonly through sexual contact.