MedPAC’s March report includes (among other things) the Commission’s annual review of the adequacy of Medicare payments in nine fee-for-service Medicare sectors. The Commission has historically reviewed four factors when looking at payment adequacy: beneficiaries’ access to care (measures of access include supply of providers and service utilization), quality of care, providers’ access to capital, and providers’ Medicare margin (a measure of the relationship between Medicare’s payments and providers’ Medicare costs).

In its examination of the inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) sector this year, MedPAC found that:

- Between 2013 and 2014, the number of IRFs nationwide grew 1.4 percent, the IRF occupancy rate remained stable at around 64 percent, and the number of Medicare FFS cases treated in IRFs grew by less than 1 percent

- Between 2013 and 2014, there was either slight improvement or no change in the IRF quality measures that the Commission tracks

- Both hospital-based and freestanding IRFs appear to have good access to capital

- In 2014, the aggregate Medicare margin increased almost 1 percentage point, to 12.5 percent

The high margin for IRFs in 2014 indicates that, in aggregate, Medicare payments substantially exceed the costs of caring for beneficiaries. But margins differ considerably across IRFs. Since 2009, the aggregate margin for hospital-based IRFs—which account for 52 percent of IRF discharges—has been at or below 1 percent, while the aggregate margin for freestanding IRFs has been 20 percent or more. Further, since 2006, the disparity between hospital-based and freestanding IRFs’ margins has been widening. The growing disparity is likely due in part to differences in cost growth.

Freestanding IRFs likely have lower costs—and higher margins—than hospital-based IRFs in part because they are more cost-efficient in the provision of care. Hospital-based IRFs may achieve fewer economies of scale because they are smaller and have lower occupancy rates, resulting in fewer total cases over which to spread costs. In addition, the generally higher cost structures found in hospitals are allocated across all of a hospital’s lines of business, including post-acute care. If there were no disparity in costs and margins across IRFs, rebasing Medicare payment rates to a level that supports the efficient provider might be necessary to prevent overpayments and to help protect the long-run sustainability of the program. The Commission has recommended this approach in other settings when payments have substantially exceeded costs.

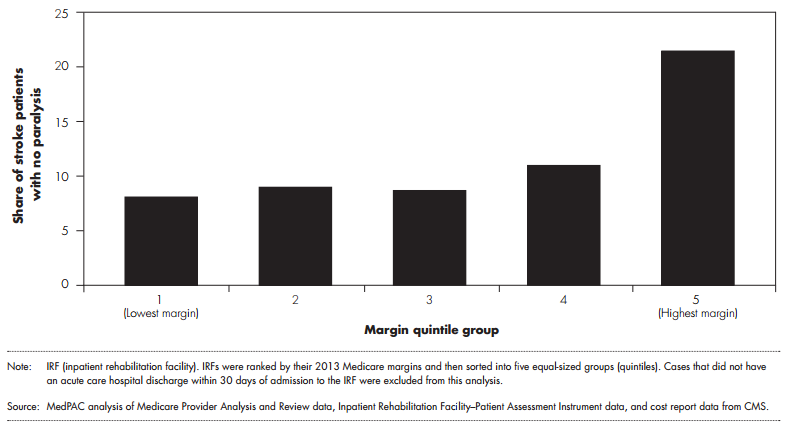

However, Commission analysis of the relationship between IRFs’ mix of cases, patient characteristics, and financial performance suggests the possibility that patient selection and assessment and coding practices may contribute to differences in profitability across providers. The Commission has found that the mix of case types in IRFs is correlated with profitability. We found that IRFs with the highest margins had a higher share of neurological cases and a lower share of stroke cases. Further, we observed differences in the types of stroke and neurological cases admitted to high- and low-margin IRFs. For example, stroke cases in the highest margin IRFs were more than two-and-a-half times more likely than those in the lowest margin IRFs to have no paralysis (figure 1). Stroke patients with paralysis typically have worse motor function than stroke patients without paralysis.

Figure 1. Stroke cases in the highest margin IRFs were more likely to have no paralysis, 2013

In addition, Commission analyses of acute care hospital claims for beneficiaries admitted to IRFs in 2013 found that patients in high-margin IRFs had, on average, a lower case-mix index in the acute care hospital, as well as a lower level of severity of illness and a shorter length of stay; they also were less likely to have been high-cost outliers in the acute care hospital or to have spent four or more days in the hospital intensive care unit. Once patients were admitted to and assessed by the IRF, however, the average patient profile changed, with patients treated in high-margin IRFs appearing to be more disabled than those in low-margin IRFs. This pattern persisted across case types (e.g., stroke).

Though differences in profitability across IRFs are driven in part by differences in underlying costs, the consistent finding that high-margin IRFs have patients who are, on average, less severely ill in the acute care hospital but appear more functionally disabled upon admission to the IRF suggests the possibility that assessment and coding practices may contribute to greater revenues in some IRFs. Providers may differ in their assessment of patients’ motor and cognitive function, resulting in payments for some IRFs that are too high relative to the costs incurred in treating their patients. To ensure payment accuracy and help improve program integrity, CMS review of IRF coding is necessary. CMS should start with focused medical record review and comparison of patients across providers, with particular focus on those IRFs that exhibit unusual patterns of case mix and coding. Over the long run, these focused medical reviews could help identify necessary reforms to the IRF payment system.

At the same time, the variation in the mix of case types by IRF profitability warrants further attention. The Commission has found that more costly cases, such as strokes, are disproportionately admitted by lower margin IRFs. Though the variation in margins across IRFs is due in part to differences in efficiency, it also appears to be related to case selection. In the near term, the Commission recommends that CMS should reduce potential misalignments between IRF payments and costs by redistributing payments within the IRF prospective payment system through an expanded high-cost outlier pool. Expanding the outlier pool would increase outlier payments for the most costly cases, thereby reducing the financial burden for IRFs that have a relatively high share of these cases. To maintain budget neutrality, the expanded outlier pool should be funded by reducing the base payment amount for all IRF cases.

We recognize that, by increasing payments for the most costly cases, Medicare may increase payments for providers who are less efficient as well as for providers who care for patients whose acuity is not well captured by the case-mix system. While this outcome is not entirely desirable, the Commission’s concern about the accuracy of Medicare’s payments for resource-intensive cases warrants this approach in the near term. Over the longer term, research is needed to assess variation in costs within the IRF case-mix groups, differences in relative profitability across case-mix groups, coding practices, and case selection. Properly calibrating payments with costs for each patient group is necessary to avoid overpayments and reduce incentives for providers to admit certain types of cases and avoid others. In the future, CMS may enact payment system reforms that warrant reassessment of IRF outlier payments and adjustments to the outlier policy, including a return to a smaller outlier pool. Ultimately, rebasing IRF payments may be necessary to prevent overpayments and help protect the long-run sustainability of the Medicare program.

In summary, reducing the base payment coupled with expanding the outlier pool will redistribute payment to IRFS that appear to be taking the most complex cases.