A recent blog post (“Correcting the Record”) from America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) provides an inaccurate description of how the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) compares spending in the Medicare Advantage (MA) program to Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) spending. The blog questions MedPAC’s long-standing assessment that, when properly compared, Medicare spends more overall for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than the program would have spent for similar beneficiaries enrolled in traditional FFS Medicare.[1] Here, we describe our method of making this comparison so that stakeholders and interested parties can understand the analytic issues that form the foundation of our conclusion and understand the shortcomings of the analysis that forms the basis of the AHIP blog post.

Consistent with our statutory mandate, MedPAC issues a report to the Congress in March of each year that examines Medicare’s payment policies and includes a chapter that provides a status report on the MA program. Since 2004, our MA status report has presented a comparison of MA and FFS spending levels. This comparison aims to make an apples-to-apples comparison by accounting for a variety of differences between the two programs, such as:

- the health status of MA and FFS enrollees,

- the geographic distribution of MA and FFS enrollees,

- Medicare spending for hospice services and graduate medical education (both direct and indirect), and

- the tendency of MA plans to submit more diagnosis codes for their enrollees, which causes the risk scores for MA enrollees to be higher than the risk scores for similar FFS enrollees.

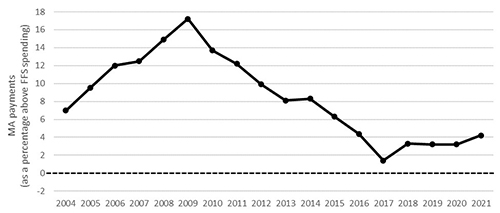

Medicare beneficiaries must have both Part A and Part B coverage to enroll in an MA plan, so another aspect of making an apples-to-apples comparison is ensuring that the FFS spending figures used in the comparison reflect costs for beneficiaries who also have both Part A and Part B coverage (or, put another way, do not include any beneficiaries who have only Part A or have only Part B). In making this calculation, we use the FFS spending figures that CMS currently uses to calculate MA benchmarks. The method that CMS uses to calculate those FFS spending figures does not fully adjust for Part A-only and Part B-only beneficiaries. CMS’s method calculates per beneficiary FFS spending separately for beneficiaries with Part A and for beneficiaries with Part B and then aggregates per beneficiary spending for the two parts. Then, because enrollees with only Medicare Part A or only Medicare Part B are healthier than beneficiaries with both Medicare Part A and Part B, CMS makes this calculation using risk-standardized spending estimates, which account for the differences in health status. In MedPAC’s March 2017 report to the Congress, we recommended that MA benchmarks be set using FFS spending only for beneficiaries with both Part A and Part B coverage, which would fully align the MA benchmarks with the program’s enrollment requirements. MedPAC estimates that making this change would increase the per beneficiary FFS spending amount by about 1 percentage point compared to the current policy. Using the same FFS spending estimates that CMS currently uses to calculate benchmarks, we find that, since 2004, MA spending has consistently been higher than FFS spending, although the difference between them has varied over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Medicare has paid more to MA plans than FFS Medicare spending would have been for the same enrollees, 2004–2021

Notes: MA (Medicare Advantage), FFS (fee-for-service). Benchmark increases under the quality bonus demonstration applied from 2012 through 2014 and under the quality bonus program applied starting in 2015. The figure reflects the Commission’s estimates of the impact of coding intensity, beginning in 2007. We conservatively assume that the coding intensity impact for 2020 and 2021 is the same as for 2019 (the most recent year of data available). MedPAC uses the figures for FFS per beneficiary spending that CMS’s Office of the Actuary generates to determine the MA benchmarks that plans use when submitting bids. Those FFS spending figures are calculated by summing (1) Part A FFS spending divided by the number of Part A FFS enrollees and (2) Part B FFS spending divided by the number of Part B FFS enrollees. This method for calculating FFS spending includes all FFS beneficiaries, including those who are enrolled only in Part A or only in Part B, and thus is not perfectly comparable to the MA population, who have both Part A and Part B. To adjust for this, CMS makes the calculation using risk-standardized spending estimates, which account for differences in health status. We estimated that calculating 2017 FFS spending only for enrollees with both Part A and Part B would yield a result that is about 1 percent higher than the estimate of spending for all FFS enrollees. Comparing MA spending with FFS spending only for enrollees with both Part A and Part B would shift the line in the graph down about 1 percentage point.

Source: MedPAC reports to the Congress 2006 through 2021.

AHIP’s blog post focuses on a slide that appeared in a staff presentation on the broader context for Medicare policy at MedPAC’s September 2020 public meeting. This presentation was part of the Commission’s work to develop the “Context for Medicare Payment Policy” chapter that traditionally appears in our annual March report. Our context chapter examines overall Medicare spending and the factors that contribute to spending growth in FFS Medicare, the MA program, and the Part D drug benefit. The slide in question focused on the growth rates for several components of Medicare spending, including MA and FFS, rather than the relative costs of covering a beneficiary in MA versus the FFS program, and thus deliberately used a different analytic method. Based on commissioner discussion at the meeting and subsequent public feedback, we have modified how this material will appear in our March 2021 Context chapter. Specifically, we made one minor improvement to the method for calculating FFS spending growth, but this revision did not significantly affect our assessment of trends in spending growth. This evolution highlights the importance of MedPAC’s public meetings, the substantive discussions at those meetings, and the public feedback we often receive afterward.

The AHIP blog post specifically noted that beneficiaries must have both Part A and Part B to enroll in an MA plan, and referred to a memorandum from Health Management Associates (HMA) that focuses on the effects of including beneficiaries who only have Part A coverage in the FFS spending estimate when comparing FFS spending to MA spending. For example, the blog post notes that including Part A-only beneficiaries would underestimate FFS spending because they have no Part B spending and because they are healthier than beneficiaries with both Part A and Part B coverage. Those are legitimate concerns, yet the current MedPAC analysis already excludes these beneficiaries from the Part B portion of spending and risk adjusts the Part A-only component. Thus, MedPAC stands by its analysis and conclusion comparing MA and FFS.

More importantly, there are several problems with the AHIP/HMA analysis that generate an incorrect conclusion about the relative spending of MA versus comparable FFS beneficiaries. First and foremost, the AHIP/HMA calculations do not account for many of the other differences between MA and FFS spending that need to be included in any apples-to-apples comparison of MA and FFS spending (Table 1). For example, the appropriate analysis would—and the MedPAC analysis does—adjust for coding intensity, different services covered (e.g., hospice), payments for graduate medical education, and the geographic distribution of beneficiaries.

Table 1: Differences in approaches to comparing MA with FFS spending

| Potential differences | MedPAC | Other (AHIP and HMA) |

| Health status | Yes | No |

| Geographic distribution | Yes | No |

| Spending for hospice and GME | Yes | No |

| Differences in coding intensity | Yes | No |

| Adjusts FFS spending for beneficiaries with Part A or Part B coverage only | Yes* | Partial** |

Notes: MA (Medicare Advantage), FFS (fee-for-service), AHIP (America’s Health Insurance Plans), HMA (Health Management Associates), GME (graduate medical education).

* MedPAC uses the figures for FFS per beneficiary spending that CMS’s Office of the Actuary generates to determine the MA benchmarks that plans use when submitting bids. Those FFS spending figures are calculated by summing (1) Part A FFS spending divided by the number of Part A FFS enrollees and (2) Part B FFS spending divided by the number of Part B FFS enrollees. This method for calculating FFS spending includes all FFS beneficiaries, including those who are enrolled only in Part A or only in Part B, and thus is not perfectly comparable to the MA population, who have both Part A and Part B. We estimated that 2017 FFS spending would be about 1 percent higher if the calculation had been limited to beneficiaries who have both Part A and Part B, and if there were no change to plan bids.

** The HMA memorandum attempts to adjust its FFS spending estimate by removing Part A-only beneficiaries, but without standardizing risk scores, causing an over-adjustment. The HMA memorandum made no attempt to adjust FFS spending for beneficiaries with only Part B coverage.

When such adjustments are made, it is clear that Medicare spending for MA beneficiaries exceeds that for comparable FFS beneficiaries.

This conclusion does not imply that MA plans are inefficient. In fact, MedPAC has long acknowledged the value of the MA program and the greater efficiency in care delivery associated with MA plans, as demonstrated in their bids. Despite greater efficiency, MedPAC continues to find that Medicare pays more for beneficiaries enrolled in MA compared to similar beneficiaries enrolled in FFS, which reflects program rules and other institutional features. Given the fiscal pressures facing the Medicare program, it is essential that Medicare pay plans appropriately so that the Medicare program and taxpayers can share in the greater efficiency in care delivery associated with MA plans. MedPAC aims to support a continued vibrant MA program that benefits Medicare beneficiaries and the Medicare program and taxpayers.

Reference

[1] America’s Health Insurance Plans. 2021. Correcting the record: Medicare Advantage costs far less than fee-for-service Medicare. February 24. https://www.ahip.org/correcting-the-record-medicare-advantage-costs-far-less-than-fee-for-service-medicare/.